Burn down charts are used a lot in giving a visual idea of the velocity of team; what has been done, what is yet to be done and an estimation of what we are likely to achieve by the end of the project.

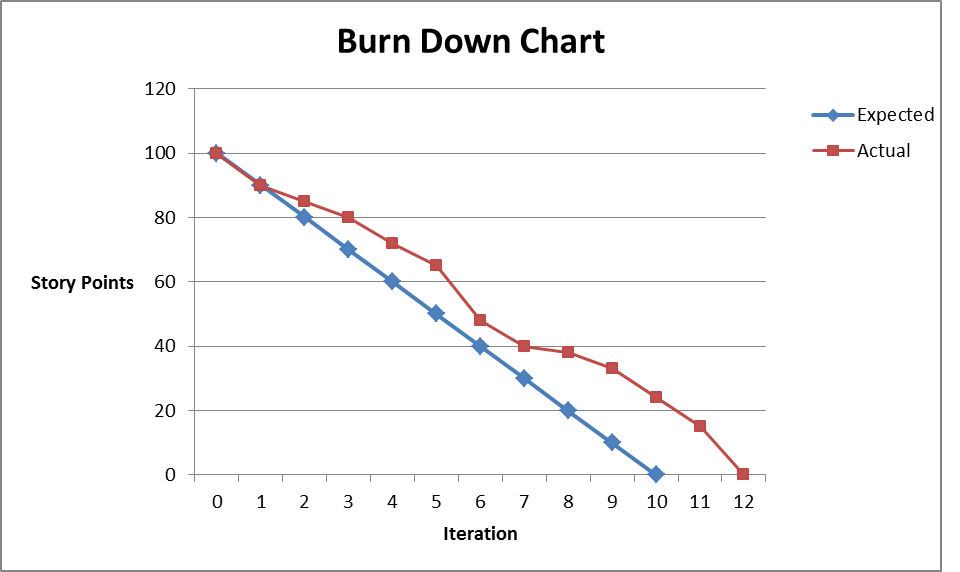

However, there seems to be a major flaw with this chart. Refer to Fig 1.0 below (click on the image to see the full chart). You will notice that with this chart, we start with a scope (total number of story points) and then based on our estimated velocity we try to determine what we expect to do by the end of the project. However, the whole idea of scrum is to say that we do not know how long this project is going to take, but we have made an estimate of how big the project is and are willing to update this as we go through sprints, because of the in-built feedback mechanism.

With the burn down chart, we start with a fixed number of points and it seems to contradict the whole idea of scrum (learn and improve as we go along).

Fig 1.0: A typical scrum burn down chart.

It is possible to alter the scope of a project while it is in progress, but it’s difficult to represent this on a burn down chart without explicitly labelling the change. Imagine that when the scrum team reaches a point where there are 60 story points remaining, the business adds 10 points to the scope of the project. If the scrum team completed 10 points of work during the sprint, they would finish exactly where they started – with 60 points left. This would create a flat line on the progress chart, giving the impression that the team had not done any work!

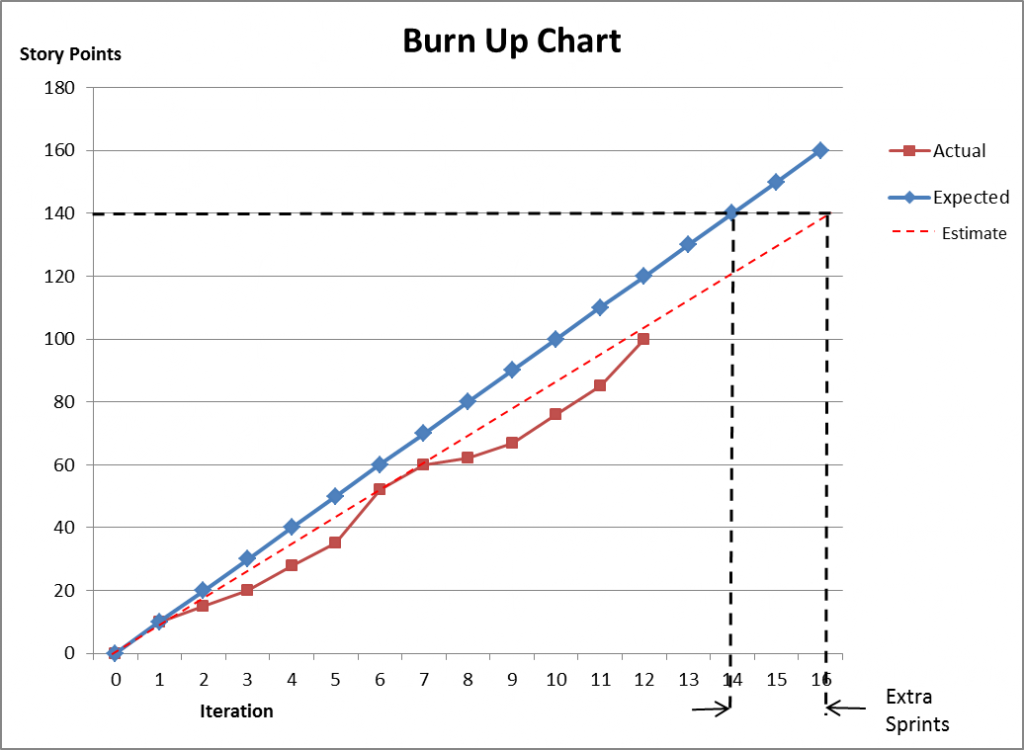

However, a burn up chart seems to be a better chart and it is rich with more information. Refer to chart 2.0 below (click on the image to see the full chart). We start from zero and as we complete a sprint we update the chart.

If the project is bounded by time we can easily tell how much work we are likely to complete by drawing a vertical line to represent the end of the project and extending the estimated burn up line to meet it.

Likewise if the project is bounded by scope we can simply draw a horizontal line from the required number of story points and extend the burn up line to get an estimate of how many sprints will be required to complete the work.

We can also easily tell how many more sprints we need if more scope is added in the middle of the project by raising the scope line.

Fig 2.0: A burn up chart showing more information than Fig 1.0 above.

In conclusion, although the burn down chart has been useful to many an agile team, using the burn up chart allows more flexibility and shows more information. Give it a try!

NB: Many thanks to Adam Shone who contributed to this article.

Hi Lawrence, agree with your article that burn ups are nicer than burn downs, but I prefer cumulative flow diagrams. Here’s an example of one: http://www.zsoltfabok.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2011/02/cfd_klipp.jpg

I think they can work within the sprint to visualise tasks moving across the board, or at the release level to show stories in the backlog through to production.

That is very interesting, can you recommend a link or an article to read more about it? It seems to me that it is a more enhanced version of a burn up chart. Any recommendations?

Hi Lawrence – here is a copy of a blog I did on the use of a cumluative flow diagram on a previous team I worked with, showing how it helped us improve our process flow in a way that burn up charts are unlikely to have helped with: http://blog.benjaminm.net/2011/07/22/removing-the-bubbles-solving-bottlenecks-in-software-product-development/

Thanks a lot for the article Benjamin.

My understanding is that in Scrum burndown charts are intended for use across a single sprint or for a release. Here they are useful because we know what tasks we need to do and how long we think that will take. So we can track progress against time.

Burndown charts are not intended for overall project tracking. This is because if you’ve said ‘we do not know how long this project is going to take’ then tracking progress against time is inevitably impossible.

I don’t think it’s a ‘major flaw’ of the chart if you use it in the wrong way and it doesn’t work.